Most coaches say weight loss should always be slow and steady. Otherwise you risk:

- Gaining all the weight back

- Intense hunger and cravings

- Low energy and bad workouts

- Muscle loss

But the other side of the coin—minimal short-term progress and months of dieting—is rarely considered.

What if somebody gets demotivated after not seeing any meaningful change out of the gate? What if somebody gets exhausted with the process after yet another month of trudging along?

Some people simply do better with a faster approach. An approach that allows for more consistent visual change AND a shorter dieting timeline. There are even people who do best with an extremely aggressive approach—an approach that allows for rapid visual change and a very short diet.

Which likely sounds the most appealing to you.

After all… who wants to diet longer than they have to? Or make “slow” progress?

Nobody, obviously. But we also have to consider the fact that very few people are willing to do the work associated with an aggressive approach. Intense hunger is inevitable. Your workouts and moods will suffer. Nutritional requirements are sky-high.

So where does that leave us? If every approach—from slow to fast—has its drawbacks?

Well, that’s exactly what we’re going to figure out today. To answer the question, “How fast should you be losing weight?”, we need to consider the specific trade-offs of every approach.

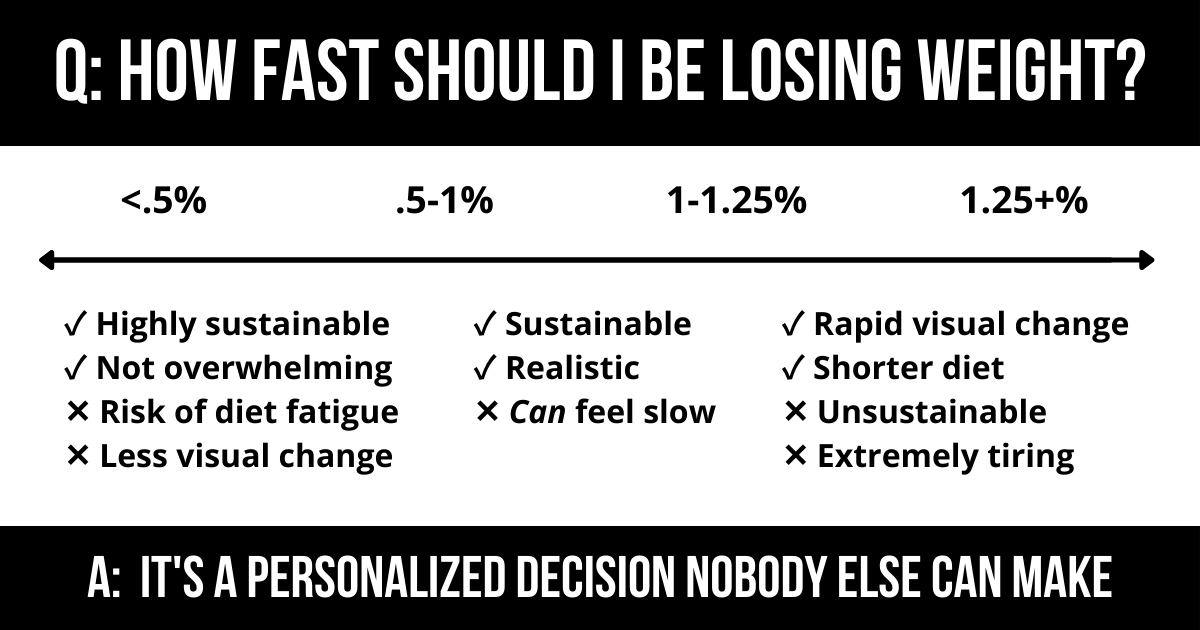

I’ve put together a simple graph to help with this (ranging from .5% of your bodyweight per week to 1.25+%):

As you can see, each approach has its pros and cons. So it’s important for us to consider your dieting history, goals, and lifestyle demands before deciding how to set up for your diet.

Let’s start by breaking down the least aggressive approach:

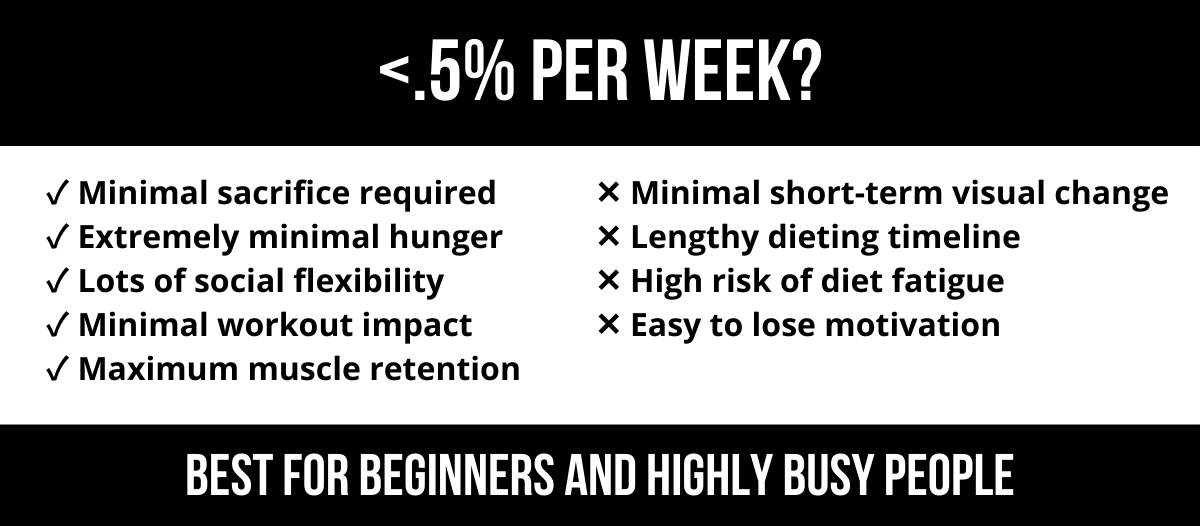

Approach #1: <.5% per week

If you’re 200 pounds and losing under .5% of your bodyweight per week, you’ll see losses under a pound. Most people complain this is “slow,” but losses of .2, .4, and .7 pounds add up faster than you think.

Take it from my very own mother, who rarely lost more than a pound per week as a client, and radically changed her life (losing 70+ pounds and 40+ inches) in just two years:

Or from Jon, who also opted for a slow and steady approach for the sake of social flexibility:

Quite honestly, most people’s efforts warrant a pace like this, as it involves:

- Fairly minimal hunger

- Lots of social flexibility

- Minimal workout impact

- Maximum muscle retention

Unfortunately, most dieters are also so impatient that they resist this reality, even if it’s the ideal pace for their hunger tolerance, willingness to sacrifice, and overall lifestyle.

—

Obviously, I recommend NOT being this type of dieter, especially if you:

- Are new to tracking your food

- Care about workout performances

- Enjoy being social and going out

- Don’t want to lose any muscle

- Hate feeling hungry

Again, increments of .3 and .6 pounds per week add up faster than you think. In just two years (0.03% of the average lifespan), you can lose 30-40+ pounds without doing anything drastic:

The drawbacks of this approach are:

- Minimal short-term visual change (something you need to get over if you’re not willing to sacrifice more)

- A potentially lengthy dieting timeline (6-12+ months)

- A higher risk of diet fatigue

- A loss of motivation (if you’re not as patient as my mother and Jon are)

All this said, I’m a fan of this approach for a lot of my VIP Nutrition Coaching clients. For others, though, a slightly faster approach is better:

Approach #2: .5-1% per week

At 200 pounds, you’ll lose 1-2 pounds per week without having to sacrifice that much more (compared to <5%). Some reasonable expectations include:

- Varying levels of hunger

- Moderate social flexibility

- Moderate workout impact

- Minimal muscle loss

- Consistent visual change

- Slightly more diet fatigue

You can see for yourself here:

Something else to consider is that the approach that’s “best” for you evolves over time.

Take it from Greg, who started in this territory (~1% per week), consciously slowed to .25-.5% per week (in an effort to NOT be restrictive during the pandemic), then ramped back up to .1% per week in recent months:

At any given time, we’ve chosen the approach that makes sense for his “season of life”—although switching things up on an extremely regular basis isn’t wise, either (I rarely alter a client’s approach more than a few times per year).

—

The reason I consider this pace “best” for most dieters is simple: it produces consistent visual change, minimizes a diet’s length, and doesn’t require extreme measures.

But there is one last route some people can take:

Approach #3: 1.25+% per week

Again, most people want to lose at this pace, but do practically nothing (consistently) to warrant it—putting them in a position to feel discouraged and frustrated. At which point, they’re left with two options:

- Lower their expectations

- Increase their efforts (a LOT)

Most people are better off choosing the former, and settling for a pace between .5% and 1% per week. This doesn’t drag out the diet, and it’s realistic for most.

That said, there are exceptions, like (A) when people who want to lose a large percentage of their bodyweight, and (B) when fairly lean, advanced dieters are in the mental, logistical, and emotional space to prioritize fat loss to an extreme degree.

For people who want to lose a meaningful percentage of their bodyweight, the process will be “easier,” as their maintenance calories are typically higher, and a large calorie deficit won’t necessarily put them in an extremely low calorie target (ex. 1,200-1,350).

For others, however, the process can be much harder. Take it from Matt, my longtime friend who came to me with an aggressive fat loss goal and a short timeline to achieve it. I warned him that he’d experience:

- Sporadically intense hunger

- Heightened cravings

- Harder than necessary workouts

- Dips in energy

He’d also need to:

- Make close to 100% of his meals

- Splurge very infrequently

- Eat a ton of protein

- Prioritize sleep quality and stress management

He was comfortable with this, executed at a high level, and earned these results:

IMPORTANT: Whether you’re somebody who’s pursuing a substantial weight loss goal, or advanced and interested in minimizing a dieting timeline (like Matt), you MUST have an “exit strategy*” for an approach this aggressive—otherwise you risk rebounding (hard).

*If you don’t know what an exit strategy is, you almost definitely shouldn’t bother with this approach (unless you’re open to some guidance).

Another thing to consider with an extremely aggressive approach is the protein demands. If you’re not getting at least one gram per pound of bodyweight, you’re risking unnecessary hunger and muscle loss.

You can combat this by requesting a copy of the Protein Power-Up, my go-to resources for dieters looking to maximize their progress:

Although any dieter will benefit from this resource, whether your goals are “aggressive” or not.

To recap the pros and cons of an aggressive approach:

It’s worth clarifying that the above considerations are mostly for advanced dieters, and that the “symptoms” of this approach are less intense for people pursuing larger weight loss goals (because of their maintenance calories).

What next?

Now that we’ve considered the trade-offs of each approach, it’s time to decide which pace makes the most sense for you:

✓ If you’re a beginner, highly social, or not overly interested in changing your habits, <.5% per week makes the most sense for you

✓ If you have some dieting experience, want to see fairly consistent visual change, and are comfortable making more sacrifices, ~1% per week is likely a good target

✓ If you’re an experienced dieter who’s able to prioritize fat loss above most other things, OR interested in losing a large percentage of your bodyweight, 1.25+% might make sense for you (IF you have an exit strategy in place)

Great. How do we ensure these paces?

The first two things you need to know are that:

- You MUST burn more calories than you consume if you want to lose weight. This is called a calorie deficit and it’s how all diets produce change (no matter how they’re marketed)

- A pound is equal to 3,500 calories

With this in mind, here’s how a 200 pound person might set up their diet to lose .5 pounds per week (.25%):

- We’ll use hypothetical maintenance calories of 3,000—meaning it takes 3,000 calories to maintain their bodyweight

- A .5 pound loss requires a 1,750 calorie deficit (half of 3,500) per week

- This breaks down to a 250 calorie deficit per day

- This person would eat 2,750 calories (3,000 – 250 calories) per day to lose .5 pounds per week

BEFORE moving any further:

The body is NOT a perfect math equation and weight loss targets are 100% out of our control. This hypothetical calculation does NOT account for a single human element (ex. stress levels and dieting history). It is nothing more than an example of what might required to lose .5 pounds per week.

Generic calendars will only get you so far

Now let’s pretend this person wanted to pick up the pace and lose 1.5 pounds per week (.75%) instead:

- A 1.5 pound loss requires a 5,250 calorie deficit per week

- We divide this over seven days and get a 750 calorie deficit per day

- This person would eat 2,250 calories (3,000 – 750 calories) per day to lose 1.5 pounds per week

Something else to consider is that very few people have maintenance calories of 3,000. Because of this, deficits over 500 (per day) aren’t typically wise. The trade-offs intensify, and it’s often unhealthy and unsustainable.

(I used a 3,000 calorie reference to keep things simple.)

Keep this in mind before we move to the final example of a 2.5 pound per week (1.25%) loss:

- A 2.5 pound loss requires a 8,750 calorie deficit per week

- We divide this over seven days and get a 1,250 calorie deficit per day

- This person would eat 1,750 calories (3,000 – 1,250) per day to lose 2.5 pounds per week

Again, there are very few scenarios where I’d recommend a deficit this large—unless somebody had extremely high maintenance calories and an exit strategy in place.

That’s why I don’t even offer hypothetically aggressive calculations for people with lower maintenance calorie in this reference chart:

It’s worth repeating that the body is NOT a perfect math equation and these are NOT nutritional recommendations. None of these estimates account for:

- Dieting history

- Stress levels

- Sleep quality

- Workouts

- Lifestyle demands

So PLEASE do not take these and run with them (it’s a recipe for failure). Use them as a educational reference and nothing more—and let me know if you’d like me to personal them for you in an ongoing coaching dynamic:

I’d be more than happy to take the guesswork out of your hands and customize a plan to your needs.

Each and every one of my clients goes through a “Primer Period” where we ensure sleep, stress, food quality, and activity levels are in check BEFORE beginning a diet (of any intensity). This elevates your maintenance calories and makes you more likely to maintain your results.

If you skip this (as most people do), your diet will be unnecessarily hard and your results won’t last.

So let me know if you’re tired of turning your wheels, and want to clear path to results like these: